https://www.americancatholic.org/Features/JohnPaulII/3-CentralAmerica-1983.asp

March 1983

The Pope in Central America: What Did His Trip Accomplish?

by Paul D. Newpower, M.M., and Stephen T. DeMott, M.M.

El Salvador: The Fratricidal War Continues

by Paul D. Newpower, M.M.

When the pope arrived in El Salvador on March 6, he insisted on visiting Archbishop Oscar Romero's tomb in spite of opposition. At the open-air Mass which followed, when the pope explained that he had just been to the cathedral, the crowd of 750,000 burst into applause. The pontiff went on to proclaim Archbishop Romero as "a zealous and venerated pastor who tried to stop violence. I ask that his memory be always respected, and let no ideological interest try to distort his sacrifice as a pastor given over to his flock." The right-wing groups did not want to hear that. They portray Romero as one who stirred the poor to violence.

The other papal gesture that drew diverse reactions in El Salvador and rankled the Reagan administration was the pope's use of the word dialogue in talking about steps toward ending the civil war. A month before John Paul II journeyed to Central America, U.S. government representatives visited the Vatican and El Salvador to persuade Church officials to have the pope mention elections rather than dialogue.

During his Mass in El Salvador, the pope directly addressed the question of a solution to the Salvadoran conflict by repeating five times the word dialogue. He also condemned any ideology "which opposes the dignity of the human person, ...sees in the use of force the source of rights, and sees the classification of enemies as the ABC's of politics." He concluded that "no one should be excluded from efforts for peace."

The night of March 6, Pope John Paul warmly encouraged the priests, brothers and sisters in El Salvador to continue to accompany the people in their sufferings—even at the cost of their lives—as others had so valiantly done before in the country of "Our Savior." He cautioned them not to be motivated by political ideologies but by faith. And he affirmed Church workers, including catechists and laity, in their courageous defense of the dignity of every person.

Guatemala: Fighting Subversion With ‘Bullets and Beans’

by Paul D. Newpower, M.M.

If Archbishop Romero and dialogue constituted the focus of the pope's visit in El Salvador, his visit in Guatemala centered around the government's execution of six "subversives" four days prior to the pope's arrival, and the plight of the indigenous peoples.

President Rios Montt extended the pope a cool reception at the Guatemala City Airport. He asked John Paul, while in Guatemala, to tell his religious to give a good example to the people and avoid partisan politics. The pontiff, in reply, reminded everyone that Guatemala, even recently, has been the scene of death and destruction.

Over a million Guatemalans cheered as the popemobile entered Guatemala City's Campo Marte for the principal Mass, driving over the final five miles of colored sawdust carpet. The overwhelming outburst of enthusiasm reflected a reaction to the suffocating fear of repression most of the common people live with.

The pope began his homily on "Faith and Social Promotion" with a theological explanation. But then, from the high altar constructed by the military, John Paul II raised his voice in protest against "the tortures, kidnappings and flagrant injustices." He insisted that the Church "has raised and will continue to raise its voice to condemn injustices and denounce attacks, especially against those who are most humble and poor—not in the name of any ideology, but in the name of Jesus Christ and his message of love, peace, justice, truth and liberty."

In Quetzaltenango, the second major city of Guatemala and a predominantly Indian area, Pope John Paul II, who arrived at the simple thatched-roof altar on the back of an open cargo truck, continued an impassioned plea for respect toward indigenous peoples. To the crowd of 750,000, many of whom had walked for days from as far away as Mexico, he said: "I ask your government for legislation that will effectively protect you from abuses. God prohibits killing. Let the sacred character of your lives be safeguarded." The pope ended his speech by encouraging the people to be the primary agents of their own promotion. He suggested they organize associations for the defense of their rights and the realization of their concerns, an action sure to be considered subversive by the government.

Nicaragua: Catholics Caught in the Middle of a Power Struggle

by Stephen T. DeMott, M.M.

The pope's visit to Central America will no doubt be remembered more for what happened in Nicaragua than for anything else. It was the first and only time that the Holy Father and crowds have engaged in an unfriendly shouting match.

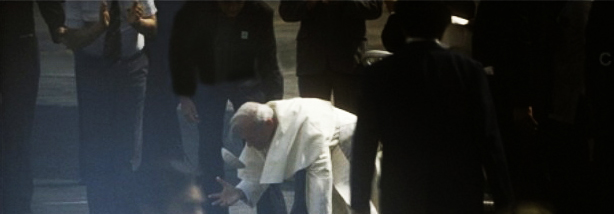

At six o'clock on the evening of March 4, just as the heat of the tropical sun was beginning to wane, the white-robed pope stood on a high platform before 700,000 people in Managua's vast July 19 Plaza, and read in strong, measured tones from a prepared text about Church unity. But less than halfway into his homily, shouts began to drown out polite, approving applause and finally the pope himself. The slogans quickly went from the ecclesiastical to the political: "We want a Church that stands with the poor!" "We want peace!" "Between Christianity and the revolution there is no contradiction!" And finally: "Power to the people!" An angry John Paul II three times yelled: "Silencio!"

The long-range implications of this unceremonious interchange are many. The strident voices heard during the papal Mass were mostly expressing disappointment and anger, but they were also a clear sign of the divisions in the Nicaraguan Catholic Church. As a result of the pope's visit, the tensions between Church and state are higher and the divisions between Catholics for and against the revolution are deeper than ever before.

Since the pope's visit, the Nicaraguan hierarchy has had less tolerance for the government and for Catholics who support the revolution. At a clergy meeting in Managua a week after John Paul II's 12-hour stay in the country, Father Uriel Molina [one of Nicaragua’s leading progressive priests] told me that the auxiliary bishop, Bosco Vivas, presented him and other pro-revolution priests with the ultimatum: "Either you are with me, the archbishop and the pope, or you can find yourselves another diocese." The Nicaraguan hierarchy's hardened attitude is also directed toward the four priests who presently hold government posts.

Honduras: ‘The Patience of the People Has Its Limits’

by Stephen T. DeMott, M.M.

High in the pine-studded hills on the outskirts of Tegucigalpa, Honduras, crowds of eager Hondurans, some starting before dawn, made the trek up the long road to the Basilica of Our Lady of Suyapa to catch a glimpse of Pope John Paul II.

The pope's homily at the basilica on the morning of March 8 was a fervent reflection on the role of the Virgin Mary, honored under various titles in Central America. John Paul II proclaimed her as "Mother" and "model" for all the faithful. Calling for a rejection of all that is contrary to the Gospel, "hate, violence, injustice, unemployment and the imposition of ideologies," the pope invited the people to work for "the promotion of the poorest," especially the most needy and marginated. "You cannot invoke the Virgin as Mother," he said, while "despising or mistreating her children."

The pope's most hard-hitting words in Honduras were never spoken. In San Pedro Sula, John Paul II left with representatives of Honduran labor unions a written message addressed to the workers of Central America. The statement reiterated some of the central themes in the papal encyclical on work (Laborem Exercens), emphasizing the "primacy of work over capital" and recognizing the injustice of many economic structures. In his document for Central American workers, the pope drew special attention to the problems of illiteracy and unemployment. He called unemployment "the scourge of the world," and noted that, in addition to its social and economic ramifications, it was also "a personal, psychological and human" problem affecting the worker's entire family. |