|

http://www.seattletimes.com/ April 11, 2005

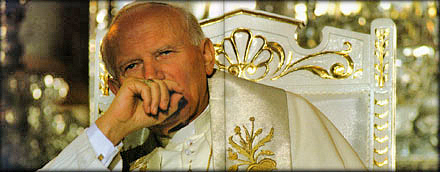

Latin American Catholics’ problem with Pope John Paul II By Chris Kraul and Henry Chu

Although the late pope promoted freedoms and denounced war and globalization, he clamped down on a movement called "liberation theology" and in so doing alienated Latin American Catholics who wanted the church to take a more active role in "liberating" the poor from misery and oppression.

LA MORA, El Salvador — Half a world away, millions of people came together last week to mourn Pope John Paul II, but you’ll hear no tearful elegies from believers like Nery Amaya, a Catholic for all of her 28 years.

As she made the rounds as a CARE volunteer in this impoverished town, she remembered the time she offered to start a parish program to help gang members. Her priest suggested that she devote her energies to Easter Week decorations instead.

Amaya charges that under the late pope, the church was too timid in its ministry to the needy, maintaining that John Paul’s efforts to put the brakes on social activism cost the Latin American Catholic Church membership and momentum in the fight against poverty and injustice.

“The church has to come down from heaven to the reality on Earth,” Amaya said. “It’s not filling my spiritual needs, and I am looking for an alternative.”

Former priest Miguel Ventura doesn’t much mourn the pope’s passing, either. The diocesan cleric left the church during El Salvador’s 12-year civil war, in which he was captured and tortured by military forces because he had organized peasants into groups to demand social justice.

“The arrival of Pope John Paul II was a step backward for El Salvador,” said Ventura, who has married and practices his own, unsanctioned brand of Catholicism as a pastor in poor northern El Salvador. “He imposed the authoritarian model on the Latin American church and didn’t have an open vision.”

In this rare interregnum before the College of Cardinals meets to select John Paul’s successor, Amaya and Ventura spoke of a disenchantment felt by many Catholic lay people and clergy in Latin America.

Although the late pope promoted freedoms and denounced war and globalization, he clamped down on a movement called “liberation theology” — and in so doing alienated Catholics who wanted the church to take a more active role in “liberating” the poor from misery and oppression.

Martyr This country reveres the memory of Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was gunned down by a right-wing death squad while celebrating Mass in 1980. Romero, who spoke out against poverty and repression, has been adopted as liberation theology’s foremost martyr, and few Salvadoran activists interviewed last week expressed affection for the pope.

Fewer still held out much hope that his successor will rejuvenate the activism they view as central to faith and social progress in the developing world.

“The church has another way of thinking now,” store owner Norma Gomez lamented as she stood outside San Salvador’s cathedral last Sunday before attending a Mass commemorating the 25th anniversary of Romero’s assassination. “The pope wasn’t with us in our time of crisis, and I don’t expect the next one to be any different.”

There are scattered signs of a revival of liberation theology, driven by desperate conditions of the poor that cry out for activism. Central to the doctrine were small communal groups that clerics such as Ventura organized to promote self-awareness and activism.

A Honduran priest has assumed leadership of an environmental movement in an area of that country devastated by deforestation. There are still 70,000 base communities in Brazil, many of them in the impoverished northeast. Priests are in the thick of the indigenous rights movement in Colombia.

But given the makeup of the College of Cardinals, the vast majority of whom were appointed by John Paul, few Vatican watchers expect the church to re-embrace liberation theology as a matter of doctrine.

Liberation theology In its heyday in the 1970s and ’80s, liberation theology sought to combine decentralized Catholicism with leftist movements for social change, to bring God into the fight for justice on Earth.

But soon after his election to the papacy in 1978, John Paul II became alarmed by what he said were similarities between some elements of liberation theology and Marxism. He saw links between the groups and the participation of some Latin American clergy in political parties, government, even guerrilla armies.

Defenders of the theology say the vast majority of priests, catechists and lay people who practiced it were apolitical and nonviolent, that John Paul’s stance was influenced by his upbringing in Eastern Europe, where communism and its Marxist underpinnings were the overriding demons.

“The pope was listening to those who were portraying liberation theology in caricatures — priests with guns, Marxists — and they just weren’t accurate,” said Dean Brackley, a theology professor at the Jesuit-run Central American University in San Salvador, the capital.

In any case, the new pope soon moved to quash liberation theology’s dynamics, without officially declaring it taboo.

In Brazil, the pope fired Archbishop Helder Camara, the so-called “red bishop,” and replaced him with an archconservative in Brazil’s impoverished northeast. He curbed the influence of São Paolo Cardinal Paulo Evaristo Arns, a strong proponent of base communities, by carving up his archdiocese in 1989.

“We were not understood,” said Arns, 83, and now retired.

Leading Brazilian liberation theologian Leonardo Boff was ordered in 1984 to explain himself before a Vatican tribunal and to observe a year of “obsequious silence” during which the Franciscan monk was forbidden to speak out publicly or publish writings. Facing another such sentence in the early 1990s, Boff later left the church.

On a 1983 visit to Nicaragua, John Paul publicly scolded priest Ernesto Cardenal, a liberation-theology proponent who had taken a post as minister of culture under the leftist Sandinista regime.

Maria Lopez Vigil, a former nun who is a journalist in Nicaragua, accused the pope of taking “the side of the powerful” in the 1970s and 1980s. “He cost the church members,” she said, “but even worse, made hundreds of thousands of people uncomfortable with a God they thought was intolerant.”

Punitive measures Here in El Salvador, where liberation theology was a driving force in organizing the resistance to repression and participation in two decades of civil war, John Paul’s punitive measures were keenly felt.

After John Paul’s ascension in 1978, Vatican commissions visited Romero two times demanding he explain his outspoken criticism of El Salvador’s military rulers and the seeming impunity of death squads that killed 21 priests and nuns.

For decades, the Vatican maintained a pointed distance from Romero and only recently announced it was initiating Romero’s beatification process.

“The pope didn’t understand the meaning of Romero,” said former priest Ventura, now 59. “It indicated that Rome doesn’t give aspects of the Salvadoran, the Latin American church the attention it should.”

Ventura says that at least 30 priests and nuns left the Salvadoran clergy after 1990 over disenchantment with Vatican policy, and he said he knows of five other ex-clerics with untraditional pastorates like his in El Salvador.

Moreover, the pope moved to more closely supervise seminary training here and to appoint conservative bishops in the aftermath of Romero’s murder. The current archbishop of San Salvador is Monsignor Fernando Lacalle, a Spaniard who is a member of the Opus Dei, a highly conservative lay organization.

Andres Santa Maria, a farmer here in La Mora, 30 miles north of San Salvador, charges that the church no longer is the advocate for the poor that it was during most of the civil conflict that ended with a 1992 peace accord.

“Monsignor Romero gave a voice to the community,” he said. “But they killed him for waking us up. And now there is no priest who denounces what goes on here, that the peace accords aren’t being observed.”

Service of poor At the very least, the cardinals who will elect the next pope appear aware that poverty and inequality will be the next pope’s top concerns.

Cardinal Claudio Hummes of São Paolo, one of those mentioned as a leading contender to succeed John Paul, said last week that the next pope needs to be “especially at the service of the poor and most excluded.”

Others insist that the legacy of liberation theology is still strong, especially in Africa and Asia.

“It is a seed that Latin America planted and that others are collecting the fruits of,” retired Cardinal Arns said this year. Brazil’s Roman Catholic Church is deeply involved with the Landless Movement, that country’s biggest grass-roots movement.

Discourse about the poor and downtrodden and the need to solve social problems is now embedded in Latin America’s Catholic church, analysts said.

Although a return to liberation theology is unlikely, Brackley, the theology professor, said the Vatican could make enormous strides if the next pope adopts at least a few of liberation theology’s features, such as decentralizing authority, adapting to local cultures and giving women a greater voice in the church.

Father Alberto Parra of Jesuit Javieriana University in the Colombian capital, Bogotá, said a resurgence of liberation theology is essential for the church to fulfill its pastoral responsibility.

“The church cannot continue to take refuge in religious elements,” Parra said. “It has to deal with social problems.”

Kraul reported from La Mora and Chu from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Los Angeles Times staff writers Richard Boudreaux and Tracy Wilkinson in Rome, Paula Gobbi in Rio de Janeiro, Hector Tobar in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and special correspondents Rachel Van Dongen in Bogotá and Alex Renderos in San Salvador contributed to this report.

|

| top |