|

|

http://www.theatlantic.com

Europe's Democratic Deficit Is Getting Worse Voter participation in European Parliament elections is low—and getting lower.

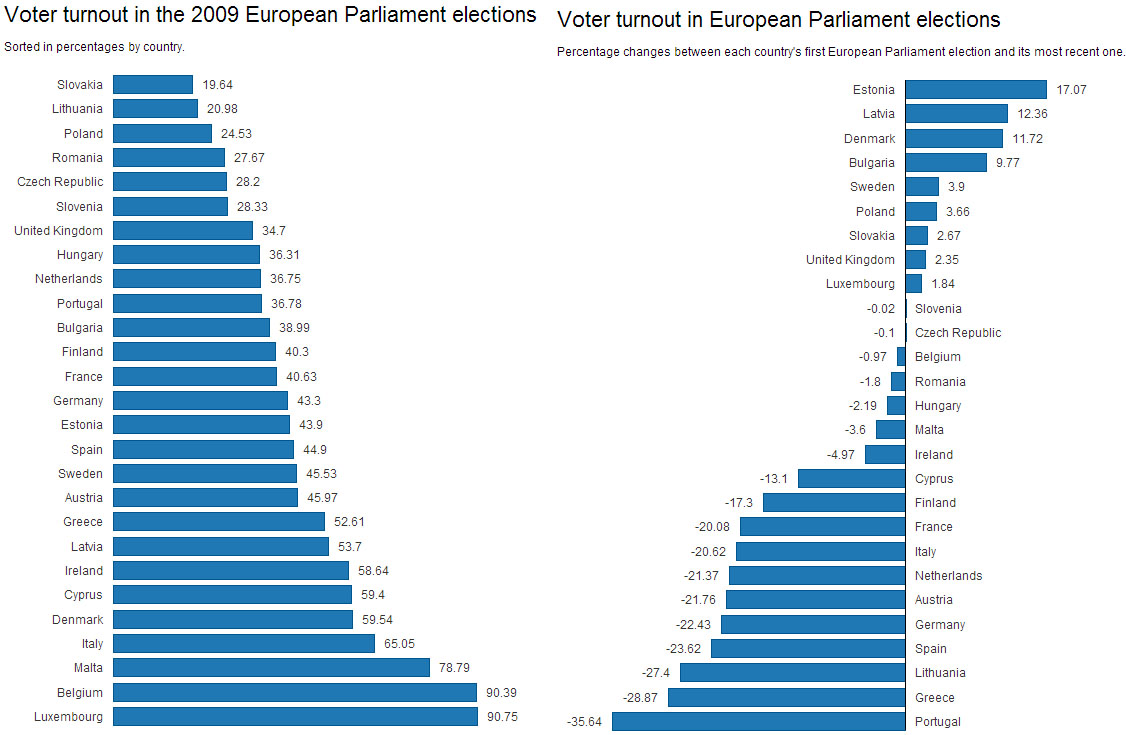

By the end of this weekend, about 380 million Europeans will have the opportunity to elect some 751 representatives to the European Parliament—the largest unicameral legislature by size of electorate. There, delegates from 28 European Union member states will play a substantial role in shaping continental policy on issues ranging from trade agreements with the United States to immigration and human trafficking. But the massive election comes at a time when the disconnect between the EU and the people it governs has arguably never been greater. A Pew Research poll this month found that majorities in seven major European countries think their voice doesn't count in the EU, including 81 percent of Italians and 80 percent of Greeks. The European Union itself acknowledges the popular perception that EU bodies "suffer from a lack of democracy and seem inaccessible to the ordinary citizen because their method of operating is so complex." It's what the institution and many others call a "democratic deficit." Here's the paradox, though: When given the chance to elect members of the European Parliament, fewer Europeans are taking the opportunity to make their voices heard than ever before. Below are voter-turnout numbers for the last European Parliament elections, which were held in 2009. (Keep in mind that some European countries, including Belgium and Luxembourg, have compulsory voting, which accounts for their astronomically high turnout numbers.) 2009 wasn't just an off year for voters, either. In the first European Parliament election in 1979, voter turnout was 62 percent. Since then, as the EU has expanded its membership, turnout has dropped in every subsequent election, falling to only 43 percent in 2009. During the U.S. general election in 2012, by comparison, voter turnout dipped by about five percentage points from 2008 to 57.5 percent. (U.S. midterm elections average roughly 40-percent turnout.) What distinguishes the U.S. from Europe in this regard is the broader historical trend. While U.S. voter-turnout rates go up and down depending on the candidates, the national mood, and so forth, the EU's voter-turnout rate has only ever gone in one direction: down. In many individual countries—but not all of them—voter participation has dropped significantly since each nation's first European Parliament election. The chart below shows the percentage-point change in voter turnout between every country's first European Parliament election and its most recent one. A negative percentage-point change indicates that voter participation has fallen.

There are several points to make here. First, a steep decline in voter turnout doesn't necessarily indicate that a country has a low voter-turnout rate. Germany's turnout has dropped by 22 percentage points since 1979 while the United Kingdom's has risen by 2 percentage points over the same period, for example, but Germany's lowest-ever voter turnout (43 percent in 2004) is still higher than Britain's highest-ever voter turnout (38.5 percent, also in 2004). Overall, many of the countries that have experienced the greatest losses in voter turnout, including Italy, Greece, Spain, and Portugal, are original or early participants in the European Parliament. Citizens of newer, smaller member states like Estonia and Latvia appear more enthusiastic about the European Parliament than those who live in older, larger member states. As a result, Europe's overall voter-turnout rate is steadily declining. For those countries that have been most harmed by the European debt crisis, the democratic deficit fuels a vicious cycle: Voters are alienated by EU policy decisions, leading them to disengage from a political process associated with those decisions, thereby giving them less influence over those decisions. Consider the relationship between voter turnout and trust in the European Central Bank. The ECB led the eurozone's fiscal response to the debt crisis, and its decisions have major ramifications for the European Union's economic policy as a whole. According to a study by the European think tank Bruegel, trust in the ECB's policies tends to correlate with voter turnout for European Parliament elections. "[The] ability to deliver financial relief through the ECB or alleviate national fiscal distress," the researchers found, "helps create a more benign attitude to Europe, leading to higher voter turnout." The EU wasn't very democratic to begin with: of the seven EU institutions recognized under its current treaty, the European Parliament is the only one directly elected by the people. But the gap between an increasingly powerful legislative body and an increasingly apathetic or openly hostile electorate is only widening. That doesn't bode well for a continent that takes pride in its tradition of representative government and liberal democracy.

|

|

|