|

|

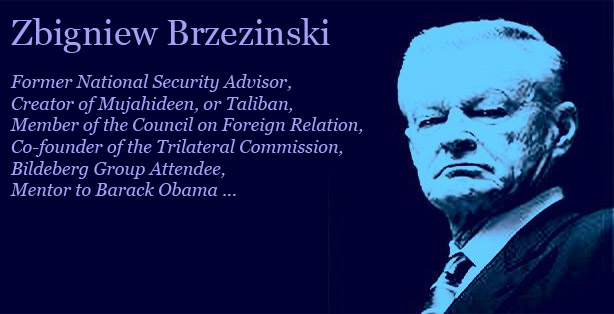

original english version below http://www.informarexresistere.fr Intervista a Zbigniew Brzezinski Zbigniew Brzezinski conferma che c’è qualcosa di sospetto e contraddittorio nel comportamento dell’amministrazione Obama sulla questione siriana e fa il nome del generale Petraeus, al tempo capo della CIA, da molti visto come l’anti-Obama dei repubblicani. Heilbrunn: Cinque anni di amministrazione Obama e lei sostiene che l’Occidente è impegnato in un’attività di massiccia propaganda. Obama si sta facendo risucchiare nel conflitto siriano perché è troppo debole per resistere lo status quo? Che cosa è successo al presidente Obama che ci ha portati a questo punto? Brzezinski: Non sono nella posizione di fare della psicoanalisi o qualsiasi tipo di revisionismo storico. Obama ha ovviamente una brutta gatta da pelare tra le mani e vi è un aspetto misterioso in tutto questo. Basta considerare la tempistica. Alla fine del 2011 ci sono scontri in Siria causati dalla siccità e fomentati da due notorie autocrazie mediorientali: Qatar e Arabia Saudita. E tutto a un tratto Obama annuncia che Assad se ne deve andare, senza apparentemente aver effettuato alcuna reale preparazione sul da farsi per fare in modo che ciò avvenga. Poi, nella primavera del 2012, l’anno delle elezioni, la CIA del generale Petraeus, secondo il New York Times del 24 marzo di quest’anno (un articolo molto rivelatore), si impegna risolutamente al fianco di Qatar e Arabia Saudita e cerca di coinvolgere in qualche modo anche i turchi in questo sforzo. Era una posizione strategica? Perché abbiamo improvvisamente deciso che la Siria doveva essere destabilizzata e il suo governo rovesciato? È mai stato spiegato questo al popolo americano?x Heilbrunn: Neocon eversori alleati dei sionisti con quale obiettivo? Brzezinski: Forse il loro punto di vista è condizionato dalla nozione, condivisa da alcuni esponenti della destra israeliana, che le prospettive strategiche di Israele siano meglio servite se tutti i suoi vicini sono destabilizzati. Mi capita di pensare che questa è una formula che, a lungo termine, porterà Israele al disastro, perché una delle conseguenze sarà l’eliminazione dell’influenza americana nella regione, con Israele che rimarrà solo. Non credo sia una buona cosa per Israele e, dal punto di vista di chi, come me, analizza i problemi dal punto di vista dell’interesse nazionale americano, non è assolutamente una buona cosa per noi. La dissoluzione totale del Libano in cinque province serve come precedente per tutto il mondo arabo, inclusi l’Egitto, la Siria, l’Iraq e la penisola arabica e sta già percorrendo quella strada. La successiva dissoluzione della Siria e dell’Iraq in aree etnicamente o religiosamente distinte, come in Libano, è l’obiettivo primario di Israele sul fronte orientale nel lungo periodo, mentre la dissoluzione del potere militare di questi stati costituisce l’obiettivo primario a breve termine. La Siria si disgregherà in diversi staterelli, in conformità con la sua struttura etnica e religiosa, come succede nell’attuale Libano. Oded Yinon, consulente del ministero degli esteri israeliano, “A Strategy for Israel in the Nineteen Eighties”, 1982 Brzezinski: Penso che se affrontiamo la questione solo con i russi, che in ogni caso va fatto perché sono parzialmente coinvolti, e se facciamo affidamento principalmente sulle ex potenze coloniali nella regione, la Francia e la Gran Bretagna, che sono davvero odiate nella regione, le probabilità di successo siano inferiori di quelle che avremmo se dialogassimo con la Cina, l’India e il Giappone, che hanno interesse ad un Medio Oriente più stabile … Insieme, quei paesi possono forse contribuire a costruire un compromesso in cui, almeno di facciata, nessuno sarà un vincitore, ma che potrebbe includere una cosa che sto proponendo da più di un anno, e cioè delle elezioni sponsorizzate a livello internazionale in Siria, in cui chiunque voglia candidarsi lo faccia, che potrebbero salvare la faccia ad Assad e che potrebbero risultare in un accordo, di fatto, in cui completa il suo mandato il prossimo anno e non si ripresenta. Heilbrunn: Altrimenti? Brzezinski: Temo che siamo diretti verso un intervento americano inefficace, il che è anche peggio. Ci sono circostanze in cui l’intervento non è l’opzione migliore, ma non è nemmeno quella peggiore. Quello di cui si sta parlando è aumentare il nostro aiuto alla meno efficace delle forze che si oppongono ad Assad. Quindi, nella migliore delle ipotesi, è solo dannoso per la nostra credibilità. Nel peggiore dei casi si accelera la vittoria di gruppi che sono molto più ostili a noi di quanto lo sia mai stato Assad. Io ancora non capisco perché abbiamo concluso, nel 2011 o nel 2012, un anno di elezioni, per inciso, che Assad doveva andarsene. Heilbrunn: La sua prima risposta su Israele era molto affascinante. Ritiene che se la regione dovesse entrare in una fase di maggiori sconvolgimenti, con una diminuzione d’influenza americana, Israele ci vedrebbe l’opportunità di consolidare le sue conquiste, o addirittura di andare oltre se anche la Giordania piombasse nel caos? Brzezinski: Sì, so dove vuole arrivare. Penso che nel breve periodo, creerebbe una grande Fortezza Israele, perché non ci sarebbe alcun ostacolo, per così dire. Ma sarebbe, innanzitutto, un bagno di sangue in misura diversa per persone diverse, con alcune perdite significative anche per Israele. Ma gli esponenti della destra sono convinti che sia necessario per la sopravvivenza di Israele. Nel lungo termine una regione ostile come quella non può essere controllata, anche da parte di una potenza nucleare. Ad Israele succederà quel che è successo a noi con altre guerre, sebbene su scala minore. Attriti, estenuazione, demoralizzazione, fuga di cervelli, e poi una specie di cataclisma, imprevedibile in questa fase perché non sappiamo chi avrà cosa e quando. Dopo tutto, l’Iran è lì vicino. Potrebbe avere qualche capacità nucleare. Supponiamo che gli israeliani se ne disfino. Pensano di fare lo stesso con il Pakistan e gli altri? L’idea che si possa controllare una regione a partire da un paese molto forte e motivato, ma con soli sei milioni di persone, è semplicemente un sogno delirante.x http://nationalinterest.org Brzezinski on the Syria Crisis Heilbrunn: Here we are five years into the Obama administration, and you’re stating that the West is engaging in “mass propaganda.” Is Obama being drawn into Syria because he’s too weak to resist the status quo? What happened to President Obama that brought us here? Brzezinski: I can’t engage either in psychoanalysis or any kind of historical revisionism. He obviously has a difficult problem on his hands, and there is a mysterious aspect to all of this. Just consider the timing. In late 2011 there are outbreaks in Syria produced by a drought and abetted by two well-known autocracies in the Middle East: Qatar and Saudi Arabia. He all of a sudden announces that Assad has to go—without, apparently, any real preparation for making that happen. Then in the spring of 2012, the election year here, the CIA under General Petraeus, according to The New York Times of March 24th of this year, a very revealing article, mounts a large-scale effort to assist the Qataris and the Saudis and link them somehow with the Turks in that effort. Was this a strategic position? Why did we all of a sudden decide that Syria had to be destabilized and its government overthrown? Had it ever been explained to the American people? Then in the latter part of 2012, especially after the elections, the tide of conflict turns somewhat against the rebels. And it becomes clear that not all of those rebels are all that “democratic.” And so the whole policy begins to be reconsidered. I think these things need to be clarified so that one can have a more insightful understanding of what exactly U.S. policy was aiming at. Heilbrunn: Historically, we often have aided rebel movements—Nicaragua, Afghanistan and Angola, for example. If you’re a neocon or a liberal hawk, you’re going to say that this is actually aiding forces that are toppling a dictator. So what’s wrong with intervening on humanitarian grounds? Brzezinski: In principle there’s nothing wrong with that as motive. But I do think that one has to assess, in advance of the action, the risks involved. In Nicaragua the risks were relatively little given America’s dominant position in Central America and no significant rival’s access to it from the outside. In Afghanistan I think we knew that Pakistan might be a problem, but we had to do it because of 9/11. But speaking purely for myself, I did advise [then defense secretary Donald] Rumsfeld, when together with some others we were consulted about the decision to go into Afghanistan. My advice was: go in, knock out the Taliban and then leave. I think the problem with Syria is its potentially destabilizing and contagious effect—namely, the vulnerability of Jordan, of Lebanon, the possibility that Iraq will really become part of a larger Sunni-Shiite sectarian conflict, and that there could be a grand collision between us and the Iranians. I think the stakes are larger and the situation is far less predictable and certainly not very susceptible to effective containment just to Syria by American power. Heilbrunn: Are we, in fact, witnessing a delayed chain reaction? The dream of the neoconservatives, when they entered Iraq, was to create a domino effect in the Middle East, in which we would topple one regime after the other. Is this, in fact, a macabre realization of that aspiration? Brzezinski: True, that might be the case. They hope that in a sense Syria would redeem what happened originally in Iraq. But I think what we have to bear in mind is that in this particular case the regional situation as a whole is more volatile than it was when they invaded Iraq, and perhaps their views are also infected by the notion, shared by some Israeli right-wingers, that Israel’s strategic prospects are best served if all of its adjoining neighbors are destabilized. I happen to think that is a long-term formula for disaster for Israel, because its byproduct, if it happens, is the elimination of American influence in the region, with Israel left ultimately on its own. I don’t think that’s good for Israel, and, to me, more importantly, because I look at the problems from the vantage point of American national interest, it’s not very good for us. Heilbrunn: You mentioned in an interview, I believe on MSNBC, the prospect of an international conference. Do you think that’s still a viable approach, that America should be pushing much more urgently to draw in China, Russia and other powers to reach some kind of peaceful end to this civil war? Brzezinski: I think if we tackle the issue alone with the Russians, which I think has to be done because they’re involved partially, and if we do it relying primarily on the former colonial powers in the region—France and Great Britain, who are really hated in the region—the chances of success are not as high as if we do engage in it, somehow, with China, India and Japan, which have a stake in a more stable Middle East. That relates in a way to the previous point you raised. Those countries perhaps can then cumulatively help to create a compromise in which, on the surface at least, no one will be a winner, but which might entail something that I’ve been proposing in different words for more than a year—namely, that there should be some sort of internationally sponsored elections in Syria, in which anyone who wishes to run can run, which in a way saves face for Assad but which might result in an arrangement, de facto, in which he serves out his term next year but doesn’t run again. Heilbrunn: How slippery is the slope? Obama was clearly not enthusiastic about sending the arms to the Syrian rebels—he handed the announcement off to Ben Rhodes. How slippery do you think this slope is? Do you think that we are headed towards greater American intervention? Brzezinski: I’m afraid that we’re headed toward an ineffective American intervention, which is even worse. There are circumstances in which intervention is not the best but also not the worst of all outcomes. But what you are talking about means increasing our aid to the least effective of the forces opposing Assad. So at best, it’s simply damaging to our credibility. At worst, it hastens the victory of groups that are much more hostile to us than Assad ever was. I still do not understand why—and that refers to my first answer—why we concluded somewhere back in 2011 or 2012—an election year, incidentally—that Assad should go. Heilbrunn: Your response earlier about Israel was quite fascinating. Do you think that if the region were to go up into greater upheaval, with a diminution of American influence, Israel would see an opportunity to consolidate its gains, or even make more radical ones if Jordan were to go up in flames? Brzezinski: Yes, I know what you’re driving at. I think in the short run, it would probably create a larger Fortress Israel, because there would be no one in the way, so to speak. But it would be, first of all, a bloodbath (in different ways for different people), with some significant casualties for Israel as well. But the right-wingers will feel that’s a necessity of survival. But in the long run, a hostile region like that cannot be policed, even by a nuclear-armed Israel. It will simply do to Israel what some of the wars have done to us on a smaller scale. Attrite it, tire it, fatigue it, demoralize it, cause emigration of the best and the first, and then some sort of cataclysm at the end which cannot be predicted at this stage because we don’t know who will have what by when. And after all, Iran is next door. It might have some nuclear capability. Suppose the Israelis knock it off. What about Pakistan and others? The notion that one can control a region from a very strong and motivated country, but of only six million people, is simply a wild dream. Heilbrunn: I guess my final question, if you think you can get into this subject, is . . . you’re sort of on the opposition bank right now. The dominant voice among intellectuals and in the media seems to be a liberal hawk/neoconservative groundswell, a moralistic call for action in Syria based on emotion. Why do you think, even after the debacle of the Iraq War, that the foreign-policy debate remains quite skewed in America? Brzezinski: (laughs) I think you know the answer to that better than I, but if I may offer a perspective: this is a highly motivated, good country. It is driven by good motives. But it is also a country with an extremely simplistic understanding of world affairs, and with still a high confidence in America’s capacity to prevail, by force if necessary. I think in a complex situation, simplistic solutions offered by people who are either demagogues, or are smart enough to offer their advice piecemeal; it’s something that people can bite into. Assuming that a few more arms of this or that kind will achieve what they really desire, which is a victory for a good cause, without fully understanding that the hidden complexities are going to suck us in more and more, we’re going to be involved in a large regional war eventually, with a region even more hostile to us than many Arabs are currently, it could be a disaster for us. But that is not a perspective that the average American, who doesn’t really read much about world affairs, can quite grasp. This is a country of good emotions, but poor knowledge and little sophistication about the world. Heilbrunn: Well, thank you. I couldn’t agree more. Fonti: http://www.iljournal.it/2013/michael-hastings-e-stato-ucciso/482704 http://www.historycommons.org/entity.jsp?entity=oded_yinon http://nationalinterest.org/print/commentary/brzezinski-the-syria-crisis-8636 http://fanuessays.blogspot.it/2011/10/verso-un-secondo-olocausto.html http://fanuessays.blogspot.it/2012/01/auschwitz-in-israele-il-secondo.html |

| top |