|

|

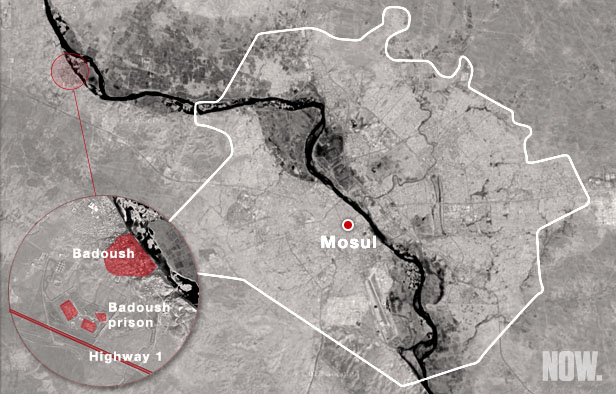

Al Hayat Prisoners of Mosul’s Badoush: 940 buried in mass graves An harrowing first-hand account of ISIS's massacre of Badoush Prison inmates on the day it captured Mosul

ERBIL — He cannot forget the muffled cries of his murdered companions from the prison, or how their dead bodies piled up on top of him, and he cannot sleep — the whistling sound of the bullets that passed close to his head haunts him every night. To this very moment, he is terrified by the memory of how the brains of the prisoner standing to his left stuck to him while he was spattered with the guts of the prisoner standing to his right. Saeed Anmar wasn’t the only inmate from Badoush Prison to survive the massacre the Islamic State (ISIS) carried out on the morning of 10 June 2014. Another witness, inmate Qasim Hamza, also survived the massacre by throwing himself into the gully where the bodies of the dead were falling. He forced himself to bear the pain of his wounds by biting down on the leg of a dead body so ISIS members wouldn’t notice he was still alive. Both Anmar and Hamza remained hidden under the bodies of the dead in Wadi Badoush during the few tense minutes it took to carry out the executions. Each of them crawled, on his own, to escape from the gully, where the bodies of 500 Iraqi prisoners now lie after ISIS executed them on the morning of that day. ISIS has, in stages, released images of most of the massacres it has committed against the people of Iraq, including the Speicher massacre, in which nearly 1,700 defenseless captives were put to death in the city of Tikrit. So far, however, the group has not released pictures or videos of the mass extermination it committed against the inmates of Badoush Prison. Neither has it admitted, in the statements it releases via the internet, to any of the massacres carried out against the prisoners. Through the testimonies of seven survivors, prison guards, eyewitnesses and prisoners’ relatives, as well as government and civilian sources, this report reveals how more than 940 out of 2,700 Iraqi prisoners were executed by ISIS. These prisoners were in detention at Badoush on the night Mosul fell to the group. Their bodies were either buried in mass graves, or left to rot at four sites the writer was unable to reach as they are still under the group’s control. The report also reveals how the Iraqi Army and guards from the Interior and Justice Ministries withdrew from the area around the prison and its interior without firing a shot, leaving the prisoners in their custody locked up in their cells waiting for ISIS to decide their fate. The story of Badoush Prison began, according to surviving prisoner Riad Mansour, at 8 p.m. on the evening of 9 June. “At the time, rumors spread about the withdrawal of the security forces tasked with protecting the area around the prison, and its gates and towers. Later we discovered that the officers and prison guards has also fled.” Prison guard Mohammad al-Hiyali confirms that most of the guards received calls from their families asking them to leave the prison and come back to their homes. “Personally, I received a call from my older brother. He told me that ISIS had taken over the city, the state had completely collapsed, and I had to come home immediately.” Al-Hiyali admits that he wasn’t prepared to die for anyone — he slipped out of the prison, accompanied by several colleagues. Another guard, Ahmad Ezzeddin, did the same. He confirms that the number of guards remaining in the prison when he left at around 10 p.m. was no more than 15 out of the nearly 100 guards who were at the prison that day. Haidar al-Saadi, spokesperson for the Ministry of Justice, says that ministry guards stationed at Badoush were unable to protect the prison and the prisoners from the inside because the security forces protecting the prison from the outside had suddenly disappeared. Before the incident, the prison was guarded by a force of approximately 1,000 soldiers and security personnel — according to ministry officials, that force included all members of the fourth regiment under the Iraqi Army’s third division, the emergency regiment of the local police, a company of transport vehicles belonging to the federal police, and a protection force made up of Justice Ministry employees. This is why Al-Saadi doesn’t believe the Ministry of Justice is responsible for what happened, and why he believes the events were caused by a general collapse of security units after Mosul fell to ISIS — the psychological effect of the city falling and the calls received by prison staff from their families contributed to them leaving the prison and returning to their homes. Before that night, the guards at Badoush Prison — most of whom are from the city of Mosul where ISIS was already active — received threats stating that they and their families would be targeted. The Ministry of Justice confirmed that 200 guards had tendered group resignations at the end of 2013 after receiving death threats. On top of this, Badoush Prison wasn’t fortified against breakouts and incursions. In December 2006, Saddam Hussein’s half-nephew, Ayman Sabawi, escaped after colluding with one of the prison guards. This was followed by the incursion Al-Qaeda carried out with the help of Baath Party groups in the spring of 2007 — an operation which lead to the escape of 186 “dangerous” prisoners, including two sons of Saddam’s half-brothers, Barzan and Watban, Al-Qaeda representative Abu Maysara al-Iraqi and 36 Arab Al-Qaeda members. The great escape Ahmad al-Sultan, a Badoush massacre survivor, says that Mosul residents interned in the prison learned late in the night via phone calls with their families that the city had fallen to ISIS, but no one could do anything. Then, in the early hours of the morning, the prisoners learned that the group’s members were on their way to the prison. At this, they banged on the doors of their cells, demanding to be let out, “but it was no use. There was no one there except the prisoners themselves.” Many of the prisoners kept in touch with their families by mobile phone. According to Ahmad al-Sultan, like many prisons in Iraq, it wasn’t difficult for inmates at Badoush to acquire a mobile phone, as long as they paid a good price to the corrupt guards. During one search carried out by security forces in August 2013, according to an official statement released at the time, a total of 750 cellular phones were confiscated from prisoners who acquired them through corrupt officers or guards for prices of up to 1 million Iraqi Dinars ($850). The doors of the women’s prison were the first to be opened. According to a witness who went to Badoush with his cousins to save his inmate brother, ISIS members arrived at dawn in military vehicles. Civilian buses bearing the group’s flag followed them and left again full of women dressed in white uniforms. Through intermediaries, the writer of this report managed to secure a call with one of the women who preffered to remain anonymous, and now resides outside Mosul. She confirmed that the ISIS members who broke the prison’s locks transported the female prisoners in three buses to an area close to the Christian town of Tel Keppe. There, they were released and each one of them was told to find their own way home. According to the inmate, all the female prisoners she knows arrived to their homes safe and sound. At around 8 a.m., as far as witness Mohammad Abdallah can remember, the prisoners managed to break the locks on the cell doors and make their way out to the prison gate. From there they headed for the Bawabat al-Sham area of western Mosul (4.5 kilometers southeast of Badoush) where they hoped to enter the city and find a way back to their hometowns in the center and south of the country. Saeed Anmar remembers how dozens of ISIS members were waiting for the prisoners when they arrived at a place known as the Badoush crossroads. The ISIS members told them they would transport them to Mosul so they could go from there to their hometowns. Indeed, as Anmar says “they transported us on three large trucks and headed towards Bawabat al-Sham.” At first the three trucks drove towards Bawabat al-Sham accompanied by vehicles belonging to the group, but they quickly changed direction and headed west on to a farm road leading towards Wadi Badoush. Almost two kilometers away from the main road, as far as Anwar can remember, the trucks stopped near the edge of the gully — a seasonal watercourse covered by sedge grasses and dried out vegetation. As soon as the prisoners were taken out of the trucks, according to the accounts of the three survivors — Anmar, Hamza and Massoud Waadallah — the ISIS members lined them up in an orderly fashion. Then the commander ordered that the prisoners be divided into two groups; the first to include Sunni prisoners and the second Shiites. At this point, according to Waadallah, the prisoners began to line up in the two groups. Dozens of Shiite prisoners joined the Sunni group, including Waadallah, because they realized the Shiite group wouldn’t escape death. Hajj Ali didn’t interrogate the people in the Sunni group. He simply ordered them to climb back on board the three trucks so they could be taken to Mosul, which that morning had become the main stronghold of the Islamic State. When the three trucks began making their way back towards the main road, according to Anmar and Hamza, the ISIS members made a list of the Shiite prisoners and gave each of them a number. Hamza was number 335 on the list, which included 519 prisoners. Anmar was number 257. The commander ordered that the Shiite prisoners be stripped of their possessions and taken to the edge of the gulley. There, two members of the group filmed the prisoners with video cameras before the other members of the group began the mass execution. The living dead Dozens of ISIS members simultaneously opened fire on the defenseless prisoners with automatic rifles and wheel mounted heavy machineguns. For several minutes “that seemed like an eternity,” according to Anmar, the machinegun blasts mowed down the prisoners one group after another. Anmar was hit in the shoulder by a single bullet. “At the time, I was standing between two prisoners. The first was hit in the head and his brains spattered all over my left shoulder. The guts of the second flew out on to my clothes from the right.” “When I threw myself into the gully,” Anmar remembers, “I could hear the muffled sound of the bullets as they penetrated the bodies, pulverizing their bones and tearing them apart. I could hear them as they fell on top of me and beside me, making snorting noises before they turned in to lifeless corpses.” Anmar could hardly stop his hands from shaking as he made trembling gestures to describe the scenario. “When the firing [squad] had [finished its work] the ISIS members opened fire a second time […] in case any of [us] were still alive, so I hid under the bodies and didn’t move.” At the bottom of the gully, a few meters away from Anmar, Hamza was also lying under the corpses. He was waiting for the ISIS members to stop shooting and leave so he could free himself from the bodies that had piled up on top of him and escape. “But instead of doing that they set fire to the dry plants at the bottom of the gully, shouting out takbirs and singing.” Before Anmar and two others who were with him could get out of the gully, the flames had begun gradually devouring the lifeless bodies. Meanwhile, on the other side of the gully, Hamza was crawling over the bodies of the dead to reach the top. “I was calling out to those who were still alive so they would get up — Daesh [ISIS] had left at last. As I passed over the group of bodies some of them were still moving, pulling themselves out from between the others then beginning to crawl with me towards the edge of the gully.” When Hamza reached a concrete pipe that crossed the farm road near the side of the gully he found three of “the living dead” who had escaped the flames before him. Before long, Hamza says, other survivors had arrived. “I couldn’t tell how many and I couldn’t stay with them, either. They were dying one after another because their bodies had been torn apart by the bullets. Me and two other survivors got out and headed west so we wouldn’t have to go back to the main road.” Before he reached an area west of Mosul Hamza was walking alone, exhausted. His two companions had bled heavily and couldn’t keep up — Hamza doesn’t know if they survived or not, but he believes a few other people probably made it out of the gully alive. Some of them could have fallen into the hands of ISIS and been killed. Others might have made their way the villages west of Mosul or fled to the Nineveh Plain before reaching Iraqi Kurdistan.

|