|

|

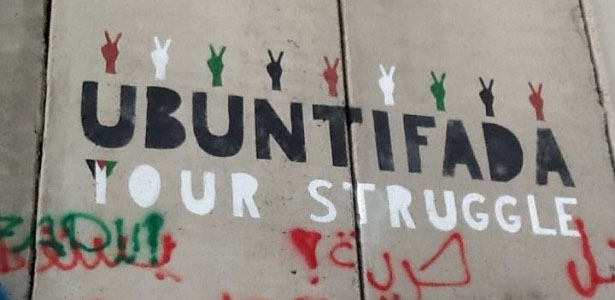

http://www.wagingnonviolence.org Perché è importante essere umani, per la gente di Gaza e del mondo UBUNTIFADA: il concetto xhosa di ubuntu combinato con la parola araba intifada graffito sul Muro di “separazione” a Betlemme può tradursi approssimativamente: elevazione della dignità umana mediante la nonviolenza. La Dr. Mona El-Farra, medico e socia della Middle East Children’s Alliance recentemente è apparsa nei titoli di Democracy Now! con il suo appello a terminare l’assalto militare a Gaza con un’affermazione potente: “Siamo esseri umani”. Ovviamente ha assolutamente ragione. A Gaza vivono esseri umani, e sembrerebbe ovvio come non mai: se non esseri umani, chi o che cosa? E perché prestiamo attenzione? Ovviamente, quello che dice effettivamente è qualcosa di ben più profondo, lo dice alla gente di Gaza; sembra che abbiamo in qualche modo dimenticato che lì ci sono esseri umani — il che solleva altre domande. Per esempio: come si possa dimenticare l’umanità di un altro e che cosa questo ci dica su chi siamo davvero? Per landare a fondo in questo tipo di domande, dobbiamo prima esplorare la dinamica di base dell’intensificarsi di un conflitto. Il conflitto, in sé, non è un tema — lo è l’immagine che abbiamo degli esseri umani con cui entriamo in conflitto. Michael Nagler, presidente del Metta Center for Nonviolence, sostiene nel suo libro del 2014 The Nonviolence Handbook: A Guide for Practical Action, (l’edizione italiana, Manuale pratico della nonviolenza, verrà pubblicato a ottobre dalle Eizioni Gruppo Abele, ndt)che il conflitto s’intensifica — cioè, si sposta sempre più verso la violenza — secondo il grado di disumanizzazione nella situazione. La violenza, in altre parole, non avviene senza disumanizzazione. Il pensiero di Nagler sulla violenza è stato in parte influenzato dal sociologo Philip Zimbardo, ch condusse un famoso esperimento di disumanizzazione controllata a Stanford nel 1971. Che accadde? Egli e i suoi studenti crearono uno scenario carcerario dove alcuni studenti assunsero il ruolo di guardie e gli altri quello di prigionieri. Zimbardo disse alle guardie di far sì che i prigionieri si sentissero isolati e “impotenti”. In sei giorni, ebbe un saggio ripensamento revocando l’esperimento perché la situazione s’era fatta psicologicamente troppo reale, perfino prossima alla tortura per qualcuno dei coinvolti. Un momento erano normali studenti di Stanford pronti a cooperare reciprocamente per un progetto. Il momento dopo, erano attanagliati in una dinamica vittima-aggressore dove il comune senso d’umanità veniva messo da parte, rendendo possibile la violenza. Per vedere esseri umani — umanizzare — ci vogliono le condizioni adatte. Quando pensiamo a esseri umani al mondo, che cosa vediamo? Un “universo amichevole”, come lo chiamava Albert Einstein? Che capiva l’estrema praticità della questione, sostenendo che se vediamo un universo non amichevole, ci vediamo dentro esseri non amichevoli. In un mondo disumanizzato di scarsità e competizione utilizzeremo tutti gli strumenti e ritrovati che abbiamo per proteggerci vicendevolmente. È arduo in un mondo di separatezza “ricordare la propria umanità e dimenticarsi del resto”, come disse Einstein. Perché mai? Guardiamoci attorno — la pubblicità, i programmi televisivi e i notiziari — e troveremo che c’è un immagine dominante degli esseri umani, non così amichevole: violenta, avida, rancorosa e felice solo quando le cose van bene per sé. Esseri alquanto superficiali, con il viso estatico quando risparmiano sull’assicurazione dell’auto e la voce monotona quando riferiscono di guerra; ossessionati con la violenza, e vogliosi di altra ancora. Vediamo e udiamo queste immagini, si dice fra 2,000 e 5,000 volte al giorno nelle aree urbane in tutto il mondo. Alla fine, le interiorizziamo. Arriviamo a pensare che quelli sono come siamo anche noi. Vedendolo così sovente, smettiamo di distinguere mentalmente fra noi e quanto ci viene proiettato. La disumanizzazione, di nuovo, è lo sfondo che rende possibile la violenza — sia direttamente, come una bomba, sia strutturalmente, come lo sfruttamento. Con l’impressione costante in mente di quell’immagine negativa dell’essere umano, pur non perpetuando violenza diretta, non possiamo negare di vivere sotto le istituzioni che infliggono violenza ad altri per noi, si tratti di multinazionali, di militari o di polizia. Queste strutture violente non spariscono perché sembrano adempiere a funzioni necessarie, come proteggerci gli uni dagli altri. In questa cornice, non c’è gran bisogno di trattare di alternative — come il peacekeeping disarmato o la giustizia restaurativa— perché semplicemente non ci raccontano la storia in cui crediamo su chi siamo e che cosa ci mette al sicuro. Una bassa immagine umana è pericolosa proprio perché manipola il nostro senso di benessere e sicurezza. Ed è anche davvero molto vantaggiosa per alcuni. Chiedete a chiunque venda armi, costruisca prigioni, o convinca le donne a mettersi un trucco che copra le “imperfezioni”. Ci hanno resi disperati: faremo o compreremo qualunque cosa prometta di renderci la nostra umanità, fintanto che conviene. Siamo pigri, inoltre, si sa, o così ci dicono. Prendendo spunto da Einstein, allora, la lotta più urgente di oggi è riprendere possesso dell’ immagine umana e ridarle dignità. Ascoltiamo che cosa ha detto solo una settimana fa Meir Margalit, ex-membro eletto del consiglio comunale di Gerusalemme per il partito Meretz e fondatrice del Comitato Israeliano contro le Demolizioni di Case: “Stiamo dimostrando non solo per Gaza, ma per tentare di salvare la condizione umana”. E la violenza, purtroppo, proprio non riesce a farlo. Se potesse, non saremmo dove ci troviamo ora, a credere che mentre una guerra si dispiega, è proprio così che agiscono gli esseri umani. Spiacenti, non c’è nulla che si possa fare salvo prendersi una sedia e stare a guardare, se vi va. La nonviolenza, d’altro canto, è una storia diversa. Se la disumanizzazione è lo sfondo per la violenza, condizione necessaria per la nonviolenza è una più elevata immagine umana. Tale storia comincia quando riconosciamo di soffrire quando altri soffrono. La psicologa Rachel MacNair ha espanso la diagnosi del ben noto Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) includendovi quello che ha denominato Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress (PITS) [Stress traumatico indotto dalla commissione di atti]. Che distingue perché, asserisce, si ritiene generalmente che il PTSD comprenda le vittime della violenza e i partecipi a quanto si potrebbe considerare un “atto crudele” o un’ “atrocità,” benché tenda a non analizzare quella che lei chiama “l’uccisione ordinaria del combattimento tradizionale”. In altre parole, mostra che la violenza non si può del tutto normalizzare — viene registrata come trauma da qualche parte nella nostra psiche, e non solo nei casi più estremi. Lo si chiami come si vuole, PITS o PTSD, il fatto che proviamo un’ansia profonda e ci traumatizziamo quando infliggiamo sofferenza ad altri è effettivamente un’osservazione che apre alla speranza. Mostra che la nostra interconnessione con e sensibilità per gli uni gli altri, è nobilitante. Mostra che seppur umano e dignità talvolta paiono un ossimoro oggi, sono effettivamente sinonimi. Ed è ora che li riconosciamo come tali. Pur essendo, dico io, intrinseca alla nostra condizione umana, la nonviolenza è un nuovo meme (elemento propagabile per mimesi, ndt). Gandhi se ne accorse quando nel 1908 coniò la parola satyagraha. Aveva un valore pratico, in quanto nuovo termine sarebbe servito a distinguere la forma di resistenza in cui stava impegnandosi da concezioni di passività. Satyagraha era qualcosa di nuovo, più profondamente trasformativo e legato a una fede implicita nella natura umana. La parola sanscrita fu costituita da due parti: satya, che significa verità, quel che è, o ancor più semplicemente, realtà; e a-graha, afferrarsi, attenersi. Nella nonviolenza, ci abbarbichiamo alla nostra dignità condivisa di esseri umani. Afferriamo, non un’illusione, ma la realtà stessa. Che cos’è la realtà? La saggezza indigena sovente l’ha riconosciuta. Il concetto xhosa ubuntu popolarizzato da Desmond Tutu durante la Commissione per la Verità e la Riconciliazione negli anni 1990 in SudAfrica si traduce grossolanamente “attraverso altri esseri umani divengo umano”. Questo ristabilisce un senso più pieno di quanto significhi essere umano. Non è una questione di nostre caratteristiche fisiche, bensì assumere una persona elevandone la natura da “tutto ciò che riesci a capire che è la violenza” a “io so solo affermare la mia umanità mediante altre persone”, il che non è possibile con la violenza. È più che una sollevazione politica, o una intifada, è un appello a elevare la dignità umana con la nonviolenza. Citando un graffito che ho visto lo scorso giugno sul cosiddetto muro di sicurezza a Betlemme, è un’ “ubuntifada.” Può darsi che si debba attingere forza dalla nostra immaginazione resistendo alla disumanizzazione, tenendo gli occhi sul problema senza sminuire la persona. Ma a quale maggior scopo può servire l’immaginazione che aiutarci a farlo? Carol Flinders afferma che è uno degli strumenti più potenti della nostra natura quando scrive “L’immaginazione sembra essere una componente vitale di un’autentica resistenza nonviolenta, permettendoci di attenerci a una visione positiva di noi stessi a prescindere da quel che il mondo dice che siamo”. Il mondo ci dice che non abbiamo potere, che badiamo solo a noi stessi e che possiamo procurarci dignità solo con la violenza; in effetti, non siamo esseri umani. Non credeteci. Siamo esseri umani e ciò ci rende potenti, perché solo esseri umani che agiscono insieme sono capaci di trasformare la violenza che ci degrada tutti.

http://www.wagingnonviolence.org August 2, 2014

Why being human matters, for the people of Gaza and the world Dr. Mona El-Farra, medical doctor and associate of the Middle East Children’s Alliance recently made headlines on Democracy Now! with her plea to end the military assault on Gaza with one powerful statement: “We are human beings.” She is, of course, absolutely right. Human beings live in Gaza, and it seems like nothing could be more obvious — if not human beings, then who or what does? And why are we paying attention? Of course, what she is really saying is something much deeper. She’s saying, that to the people in Gaza, it seems like we have somehow forgotten that human beings are there — and that raises more questions. For example: How could one forget the humanity of another and what does it tell us about who we really are? For insight into these questions, we might first explore the basic dynamic of conflict escalation. Conflict, in itself, is not at issue — it’s the image we have of the human beings with whom we engage in conflict. Michael Nagler, president of the Metta Center for Nonviolence, maintains in his 2014 book, The Nonviolence Handbook: A Guide for Practical Action, that conflict escalates — that is, moves increasingly toward violence — according to the degree of dehumanization in the situation. Violence, in other words, doesn’t occur without dehumanization. Nagler’s thinking about violence was partially influenced by sociologist Philip Zimbardo, who famously conducted an experiment in controlled dehumanization at Stanford in 1971. What happened? He and his students created a prison scenario where some students took the role of the guards and the others as the prisoners. Zimbardo told the guards to make the prisoners feel isolated and that “they had no power.” In six days, he used his better judgment and called off the experiment because the situation had become too psychologically real, even close to torture for some involved. One minute, they’re regular Stanford students ready to cooperate with one another for a project. The next, they’re locked in a victim-aggressor dynamic where common humanity was cast aside, making violence possible. In order to see human beings — to humanize — we need the conditions for it. When you think of human beings in the world, what do you see? Do you see a “friendly universe,” as Albert Einstein called it? He understood the utter practicality of this question, arguing that if we see an unfriendly universe, we see unfriendly beings living in it. In a dehumanized world of scarcity and competition we will use all of the tools and inventions we have to protect ourselves from one another. It’s hard in a world of separation to “remember your humanity and forget the rest,” as Einstein said. Why is that? Look around you — at advertisements, television programs, and the news — and you will find that there is one image of the human being that dominates, and he’s not very friendly. He is violent, greedy, hateful and only happy when things are going well for him. He’s really quite superficial — his face is ecstatic when he saves on his car insurance and his voice is monotonous when he reports on war. He’s obsessed with violence, and hungry for more. We see and hear these images, some say between 2,000 and 5,000 times a day in urban areas worldwide. Eventually, we internalize it. We come to think that this is who we are too. We see it so often, our minds stop distinguishing between ourselves and what is being projected at us. Dehumanization, again, is a backdrop making violence possible — both directly, like a bomb, and structurally, like exploitation. By constantly imprinting that negative image of the human being in our minds, even if we don’t perpetuate direct violence, we certainly can’t deny that we live under the institutions that inflict violence on others for us, be it corporations, the military or the police. These violent structures do not go away because they appear to fulfill necessary functions, like protecting us from each other. In this framework, there is little need for discussion about the alternatives — such as unarmed peacekeeping or restorative justice — because they are simply not telling the story we believe about who we are and what makes us safe. A low human image is dangerous precisely because it manipulates our sense of well-being and security. It is also extremely profitable for some. Ask anyone who sells weapons, builds prisons, or convinces women to wear makeup that covers their “imperfections.” We’ve been made desperate: We’ll do or buy anything that promises to restore our humanity to us, so long as it’s convenient. We’re lazy, too, you know, or so we’re told. Taking a cue from Einstein, then, the most urgent struggle of today is to reclaim the human image and restore its dignity. Listen to what Meir Margalit, former elected member of the Jerusalem City Council for the Meretz Party and a founder of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, said only a week ago: “We are demonstrating not only for Gaza, but to try and save the human condition.” And violence, unfortunately, just can’t do that. If it could, we wouldn’t be where we are today, believing that while a war unfolds this is just the way that human beings operate. Sorry, there is nothing you can do but pull up a chair and watch if you’d like. Nonviolence, on the other hand, is a different story. If dehumanization is the background for violence, a higher human image is the necessary condition for nonviolence. The story begins when we recognize that we suffer when others suffer. Psychologist Rachel MacNair expanded upon the widely known Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD, diagnosis to include what she named Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress, or PITS. She makes this distinction because PTSD, she argues, is generally thought to include the victims of violence and those who have been party to what one might think of as a “gruesome act” or “atrocities,” though it tends to stop short of the analysis of what she refers to as “the ordinary killing of traditional combat.” In other words, she is showing that violence cannot be fully normalized — it registers somewhere in our psyches as trauma, and not only in the most extreme cases. Call it what we want, PITS or PTSD, the fact that we experience deep anxiety and traumatize ourselves when we inflict suffering on others is actually an extremely hopeful comment. It shows that our interconnectedness with, and sensitivity to one another, is ennobling. It shows that while human and dignity sometimes seem like an oxymoron today, they are actually synonymous. And it’s time that we recognized them as such. Despite it being, as I argue, native to our human condition, nonviolence is a new meme. Gandhi saw this when, in 1908, he coined the word satyagraha. It had a practical value, being a new term that would serve to distinguish the form of resistance in which he was engaging from conceptions of passivity. Satyagraha was something new, something more deeply transformational and tied to an implicit faith in human nature. The Sanskrit word was built of two parts: satya, which means truth, that which is, or even more simply, reality; and a-graha, to grasp, hold to oneself. In nonviolence, we are clinging to our shared dignity as human beings. We are grasping, not illusion, but reality itself. What is that reality? Indigenous wisdom often recognized it. The Xhosa concept ubuntu popularized by Desmond Tutu during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the 1990s in South Africa is roughly translated, “Through other human beings, I become human.” This is restoring a fuller sense of what it means to be human. It is not a question of our physical characteristics; instead, it takes a person and elevates her nature from “all you can understand is violence” to “I can only affirm my humanity through other people,”which is not possible through violence. This is more than a political uprising, or intifada, it’s a call to uplift human dignity through nonviolence. To quote from graffiti I saw this past June on the so-called security wall in Bethlehem, it’s an “ubuntifada.” We may need to draw strength from our imaginations as we resist dehumanization, keeping our eyes on the problem without demeaning the person. But what greater purpose can the imagination serve than to help us do that? Carol Flinders affirms that it is one of the most powerful tools of our nature when she writes, “Imagination seems to be a vital component of genuine nonviolent resistance, for it allows us to hold on to a positive view of ourselves no matter what the world tells us we are.” The world is telling us that we have no power, that we only care about ourselves and that we can only get dignity through violence; in effect, we are not human beings. Don’t believe it. We are human beings and that makes us powerful, because only human beings working together are capable of transforming the violence that degrades us all. |